Hidden Heritage

Pikk Street HIDDEN HERITAGE

Compiled by Karola Mursu

Photographs by Tõnu Tunnel

360° photos by Taavi Varm

Historical photos: Estonian History Museum, Estonian Museum of Architecture, Tallinn City Museum

The varied architecture of Pikk Street takes the visitor on a journey through time, from the medieval merchant’s house to the grand urban residences of the early 20th century. Many of the buildings here are layered: one need only pause and look closely to notice medieval carved stone details, pointed Gothic portals, flowing baroque volutes or neoclassical references to antiquity – often on the very same building. Each era has left its mark on the facades, turning them into a rich and captivating book of history.

The interiors of these houses offer their own discoveries. In many cases, the medieval floor plan and old stone staircases have survived. Beneath later renovations and finishes, one may find carved stone window posts, family coats of arms etched in stone, ceiling and wall paintings, and more.

The exhibition Pikk Street Hidden Heritage presents a selection of culturally significant interiors and details that remain unseen – and often unknown – to those walking along the street. The exhibition invites us inside these houses to get to know them more intimately. Some are open to visitors, while others remain hidden behind private walls and are accessible only through this exhibition.

Pikk Street near the Green Market. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

View of Pikk Street (on the left) from the Green Market. (Tallinn City Museum)[1]

Drawings of Pikk Street by Teddy Böckler from 1964. (Tallinn City Archives)[2]

[1] View of Pikk Street from the Green Market. Tallinn City Museum, File No TLM F 10854. Museums Public Portal: https://www.muis.ee/museaalview/3113527 accessed 29. VII 2025).

[2] Pikk 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43. Drawing by Teddy Böckler from 1964. Tallinn City Archives, File No TLA.1443.1.87. Nationa Archives of Estonia: https://www.ra.ee/dgs/browser.php?tid=345&iid=124020539367&lst=2&idx=1&img=tla1443_001_0000087_00001_t.jpg&hash=8cc1ff011ee8bc6f7e782bca842a5fec(accessed 29. VII 2025).

PIKK 43

The building at Pikk 43 / Vaimu 1 is one of the tall, steeply gabled houses in Pikk Street, pointing to its medieval origins. Dendrochronological analysis has confirmed that the timber used for the roof structure – which has survived to this day – was felled in 1434.[3]

The original plot extended across the entire block, bordered by Pikk Street on one side, Vaimu Street on the flank and Lai Street at the rear. Over the centuries, it has been home to a number of notable residents, including Hans Stampell, a city councillor and member of the Blackheads merchants’ association (late 16th century); Jacob Stampell, alderman of the Great Guild (17th century); and Jacob-Johann von Patkull, a captain, military officer and nobleman (late 18th century).

In 1913, industrial and warehouse facilities for the A. Le Coq brewery and soft drinks factory were established in the building facing Vaimu Street. Later, it housed a radio station that broadcast Estonia’s first regular radio programme in 1926. From 1940 onwards, the building was used for storage and industrial purposes, including a lampshade factory, a toy repair workshop, and services for repairing umbrellas, cameras and calculators. Today, the building contains flats and commercial premises.

Although the rhythm of the windows and doors was later altered (mainly under the influence of standardised facades in the first half of the 19th century), the high triangular gable, the blind niches set into it and the fragment of a gothic carved portal all point to the building’s medieval origins. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

The decorative scheme, inspired by Pompeiian wall painting, features wall surfaces divided into framed sections and patterned bands. This style grew popular throughout Europe starting in the early 19th century, following the discovery and excavation of Pompeii. The detailing and design language of the Pikk 43 murals reflect the diversity and eclecticism of late 19th-century styles.

A stencilled frieze of alternating lotus flowers and plant motifs runs along the top of the wall. Below this, the wall is divided into sections by gold-painted frames in a historicist style. The colour scheme is vivid and contrasting – shades of blue-green, brown, pink and gold. Fine, delicately drawn details bring the wall to life and add a sense of depth to the otherwise narrow room.

In the 2020s, wall paintings, most likely dating from the second half of the 19th century, were discovered in one of the street-facing first-floor rooms. Unfortunately, the decorative scheme survives only on the upper part of the wall, leaving the lower section open to the viewer’s imagination. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[3] Tallinn, Pikk 43 / Vaimu 1. Historical report. Vana Tallinn, 1992. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n3 4711.

PIKK 52

Pikk 52 (including the part of the building facing Sulevimägi Street) spans three historical plots first mentioned between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. The original buildings were wooden houses, one of which belonged to the sexton of St Olaf’s Church. In the 15th century, these were replaced with typical merchant dwellings featuring the standard diele-dornse layout. One of the houses was likely destroyed during the Great Northern War.

In 1838, when the plots came into the possession of Dorothea, daughter of merchant Adolf Finck, the historical properties were consolidated and two of the houses were joined together. A major renovation followed in 1880 (architect Erwin Bernhard), giving the building its fashionable neo-Gothic appearance. The result was a modern apartment building with spacious and prestigious flats facing Pikk Street, while the side facing Sulevimägi Street was more modest. The latter also housed the kitchen stairwells serving the Pikk Street flats.

During the Soviet period, the building housed offices and apartments. In the 1980s, it was returned to residential use.[4]

Today, the building functions as an apartment block, with commercial premises on the lower floors.

The neo-Gothic appearance of Pikk 52 dates from the 1880 renovation (architect Erwin Bernhard). The renovation followed the latest architectural trends, and the large apartments opening onto Pikk Street were both modern and distinguished. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Architectural project of the building, dated 1880. (Tallinn City Archive)[5]

During renovation works in the 1980s, a wall painting imitating marble blocks was discovered behind timber panelling in the corner of the stairwell. The painting was documented and covered with new layers of finish. Residents knew of its existence, but it had vanished from sight. In 2015, new surveys of the finishes led to the rediscovery of the marble-effect painting. Beneath it, an earlier layer of faux-marble decoration was found partially intact. The underlying layer was documented, and the upper marble-effect painting was restored. The painting most likely dates from the late 19th or early 20th century.[6] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Wall paintings were also discovered in the vestibule on the Pikk Street side. These were done in a Pompeiian style, part of a decorative approach popular during the historicist period, with the wall divided into colour-blocked zones. The finish likely dates from the 1880s renovation.[7]

The murals are covered by another layer of art nouveau wall paintings which, due to their poor condition, were not restored. However, a cleaned section (sondage) has been left visible.[8]

(Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room with marble-effect paintings. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room with Pompeian-style paintings. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[5] Architectural project of the building, 1880. Tallinn City Archive, File No TLA.1443.002.0000014.00010.T.

[6] E. Mölder, “Ühe vanalinnamaja pidulik trepikoda.” – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2019. Tallinn: National Heritage Board, Tallinn Cultural Heritage Department, Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Heritage Protection and Conservation, p. 54. National Heritage Board website: https://www.muinsuskaitseamet.ee/sites/default/files/documents/2024-02/Muinsuskaitse%20aastaraamat%202019.pdf (accessed 20 June 2025).

[7] S. Pihlak, Tallinn Pikk 52 / Sulevimägi 8 muinsuskaitse eritingimused. Lisa 1. Tallinn, 2006. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.4510A, p. 5.

[8] E. Mölder, “Ühe vanalinnamaja pidulik trepikoda.” – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2019. Tallinn: National Heritage Board, Tallinn Cultural Heritage Department, Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Heritage Protection and Conservation, p. 54. National Heritage Board website: https://www.muinsuskaitseamet.ee/sites/default/files/documents/2024-02/Muinsuskaitse%20aastaraamat%202019.pdf (accessed 20 June 2025).

PIKK 53

The property was first recorded in archival sources in 1432, when it was separated from a larger plot (now Pikk 40). By the end of the century, a “small house” on the site is mentioned as belonging to prosperous artisans – first a tailor (1559), then a pin-maker and a shoemaker, and later, merchants. In the early 20th century, the property was purchased by Georg F. Stude, who established a marzipan, chocolate and confectionery workshop on the building’s first floor.

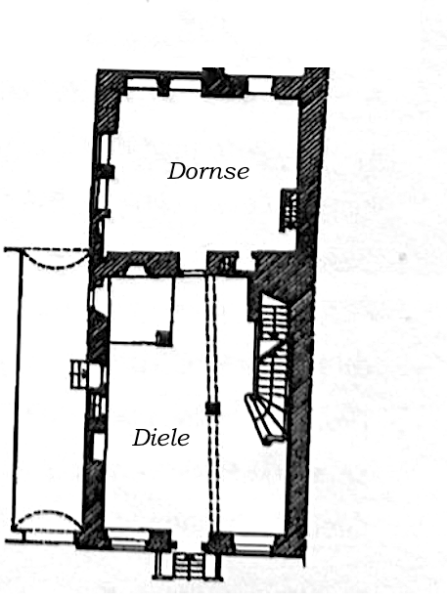

The residential building, likely built in the 15th century, retains the two-room layout typical of townhouses of that time: the diele or front room faced the street, while the dornse looked onto the courtyard. The former location of a mantel chimney running through all three floors can still be discerned in the centre of the building.[9]

But there is more to discover. At the turn of the millennium, during the removal of a later plaster ceiling in one of the first-floor rooms, a canvas ceiling painting (plafond) was discovered. Based on stylistic analysis, the baroque mural has been dated to the period between 1740 and 1790. At its centre is an allegorical composition depicting Caritas – charity and mercy. The patron and exact date of the ceiling commission remain unknown. It has been speculated that the building may have once belonged to an artist who painted the ceiling as a personal embellishment of their home.

When the plafond was removed, another painting was discovered beneath it – a wooden beamed ceiling decorated with baroque acanthus ornamentation. However, the earlier layer was in such poor condition that it was preserved and left hidden under the canvas mural, to be rediscovered by future generations.

The house was likely built in the 15th century, while its facade dates from a later remodelling in the second half of the 18th century. It combines elements of the baroque (the front door, roof form and small-paned windows on the upper floors) with the emerging classicist style (the arrangement of windows and stucco decoration).[10] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The central element of the baroque mural (circa 1740–1790) is an oval frame containing a woman nursing a child, two putti (cherubs) and a woman in a grey cloak holding a cross, chalice and Bible. The composition is an allegory of divine or neighbourly love and mercy (Caritas), often represented in art by the motif of a mother with children. Such Christian imagery aimed to cultivate the viewer’s moral values. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The oval frame is surrounded by garlands of flowers, baskets of fruit, rocaille motifs and four Dutch-style landscape paintings. The shorter sides of the ceiling feature three marbled panels.[11] The cornice – painted to imitate marble – conceals the transition between wall and ceiling. Nail holes and remnants of canvas thread beneath the cornice suggest that canvas, possibly painted, once covered not only the ceiling but also the walls and window reveals of the room.[12] (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Close-up view of the central figures. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

[9] L. Künnapu, AS Tallinna Restauraator. Arhitektuuri-ajaloolised eritingimused. Tallinn, Pikk 53 teise korruse korteri rekonstrueerimiseks. Tallinn, 1996. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n1 507, p. 2.

[10] T. Linna, AS Linnaprojekt. Pikk tn 53 arhitektuuriajaloolised eritingimused. Tallinn, 1994. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n3 200, p. 4–5.

[11] T. Linna, AS Linnaprojekt. Pikk tn 53 arhitektuuriajaloolised eritingimused. Tallinn, 1994. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n3 200, p. 4.

[12] S. Volmer, OÜ Vana Tallinn. Pikk tn. 53 lae restaureerimise aruanne. Tallinn, 2001. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n12 290, p. 2.

PIKK 55

The house fronting Pikk Street at this address was likely built in the 14th century. Its original layout – typical of medieval dwellings with the diele-dornse room arrangement – remains discernible despite later alterations. The grand Gothic stone portal facing the street (second half of the 15th century) also attests to the building’s age.

The house has had notable owners, including the descendants of Lieutenant General B. C. Kagelmann, who served under Peter I (late 18th to early 19th century), and Count Magnus de la Gardie (mid-19th century). For a long time, the Pikk 55 property was joined with its neighbour, Pikk 53. As in the adjacent building, Georg Stude’s marzipan and confectionery factory operated here in the early 20th century.

Today, the house stands empty and stripped bare, like a skeleton: its sturdy limestone outer walls (likely from the 14th century) remain intact, along with baroque painted beam ceilings (second half of the 18th century) and a grand staircase in the former diele (early 20th century).[13] From the courtyard-side dornse, one can look up from the first floor through four storeys to the roof ridge. In between, most of the ceilings and walls have collapsed. Scattered beams criss-crossing the interior offer a glimpse of times past and feed the imagination with visions of what once was – and what might one day be.

The first record of the property dates from 1365, and the street-facing dwelling was likely built around that time. The building reached its current overall volume in the 15th century. The arrangement of the second- and third-floor windows reflects the standardised facades of the early 19th century. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

From the courtyard-side dornse, one can look up from the first floor through four storeys to the roof ridge. The baroque ceiling paintings likely date from the 17th or 18th century. On close inspection, two distinct layers of paintings can be seen on the beams. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The first layer features red moresque ornamentation – a calligraphic, arabesque pattern of intertwining foliage on a yellow background, a style common in the early 17th century.[14] This layer survives only in fragments and is overlaid by a second, darker layer.

The second layer of ceiling paintings features swirling acanthus vines on a dark background, interspersed with geometric motifs,[15] and probably dates from the 18th century.

Strips of canvas hang down from the beams – these were traditionally used to conceal cracks caused by the drying of the wood. The beams were covered with canvas and then painted over to produce a smooth and decorative finish. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

The former medieval diele has been transformed into a grand vestibule. Visitors are welcomed by a sweeping staircase flanked by symmetrically placed Ionic columns and, on either side of the stairs, allegorical bas-reliefs. The interior dates from the 1920s.[16] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The left-hand relief depicts Vulcan, symbol of industry, wielding a blacksmith’s hammer while two putti roll a gearwheel toward him.

The right-hand relief shows Mercury, representing commerce, accompanied by two putti carrying parcels. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[13] AS Vana Tallinn. Tallinn, Pikk t. 53/55. Projekteerimise lähtematerjal hoonete restaureerimiseks. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n3 200.A, p. 2.

[14] K. Kodres, Ilus maja, kaunis ruum. Kujundusstiile Vana-Egiptusest tänapäevani. Tallinn: Prisma Prindi Kirjastus, 2001, p. 71.

[15] K. Matteus, R. Soodla, Tallinna vanalinna maalitud talalagede inventeerimine ja katalogiseerimine. Bachelor’s thesis. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2006, p. 14.

[16] S. Lindmaa-Pihlak, OÜ Stenhus, Tallinn, Pikk 53/55. Muinsuskaitse eritingimused. Tallinn, 2003. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9 2329, no pagination.

PIKK 59

In the early 20th century, Tallinn aspired to a metropolitan atmosphere and a modern urban lifestyle. Following the example of European cities, large stone apartment buildings of three to five storeys began to appear. Contemporary newspapers even dubbed them “skyscrapers”.[17] The first of these was completed in 1912 as a rental property for Englishman William Tulip, located at Pikk 59 / Pagari 1 / Lai 44 (architect Hans Schmidt).[18]A historic Hanseatic League office building and a medieval merchant’s house were demolished to make way for the new development. The plot was extended to Pagari Street, and the resulting building now occupies the entire end of the block bounded by Pikk, Lai and Pagari Streets.[19]

The luxury flats, with six to eight rooms each, had family quarters facing the street and servants’ rooms and kitchens on the courtyard side. The lower floors housed commercial and utility spaces. The building was equipped with all the modern conveniences of the time: central heating, flushing toilets, baths and lifts.[20]

In 1918, the building was purchased by the Naval Fortress of Peter the Great to house its senior staff. In the decades that followed, the property was successively taken over by Estonian, German and Soviet security agencies. Major alterations were made in the 1920s, including the installation of central corridors running through all floors,[21] and again in the 1940s, when prison cells were built in the basement.

In 2010, the building passed into private ownership and was renovated and converted into apartments, with commercial premises on the basement level.

The building follows the traditional formal language of classical architecture, enriched with art nouveau elements. The facade is articulated with arched bay windows and a concrete cornice between the fourth and fifth floors and adorned with medallions depicting deities from classical mythology. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Architectural project of the building, dated 1911. (Tallinn City Archive)[22]

Before the construction of the large rental building at Pikk 59, the historical Hanseatic office building and a medieval merchant’s house that stood on the site were demolished, and the property was expanded to reach Pagari Street, so that the building now extends to the end of the block between Pikk, Lai, and Pagari Streets. (Photos: Tallinn City Museum)[23][24]

One of the defining features of grand early 20th-century city buildings was the vestibule – an elegant corridor and staircase that welcomed visitors and conveyed the dignity of the building and its residents. The overall impression was shaped by numerous details: stone parquet, limestone stairs, ornate double doors with bevelled glass, art nouveau window frames, and crowning it all, the essential emblem of modern living, the lift.

The historic lift was restored during the renovation works of the 2000s. Its timber casing and metal railing were conserved. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Details from the vestibule. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the historic elevator. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[17] K. Hallas-Murula, Kõrgemale, kõrgemale, kõrgemale! Eesti 1920.–1930. aastate „pilvelõhkujad“. – Pööning No 2 (38), 2023, p. 33.

[18] K. Hallas-Murula, Tallinn teel suurlinnaks. – Eesti kunsti ajalugu 5. 1900–1940. Edited by Kodres, K. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2010, p. 210.

[19] M. Eensalu, Uhke Pagari 1. – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2013. Tallinn: National Heritage Board, Tallinn Cultural Heritage Department, Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Heritage Protection and Conservation, p. 10.

[20] M. Eensalu, Uhke Pagari 1. – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2013. Tallinn: National Heritage Board, Tallinn Cultural Heritage Department, Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Heritage Protection and Conservation, p. 10.

[21] M. Eensalu, Uhke Pagari 1. – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2013. Tallinn: National Heritage Board, Tallinn Cultural Heritage Department, Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Heritage Protection and Conservation, p. 10.

[22] Architectural project of the building, 1911. Tallinn City Archive, File No TLA.1443.002.0000097.00009.T.

[23]Tallinn, Pikk 59. Photo: N. Nyländer, Tallinn City Museum, File No TLM F 93. Museums Public Portal: https://www.muis.ee/et/museaalview/1581071 (accessed 30 July 2025).

[24] Tallinn, Pikk 59. Photo: N. Nyländer, Tallinn City Museum, File No TLM F 93. Museums Public Portal: https://www.muis.ee/et/museaalview/1581071 (accessed 30 July 2025).

PIKK 68

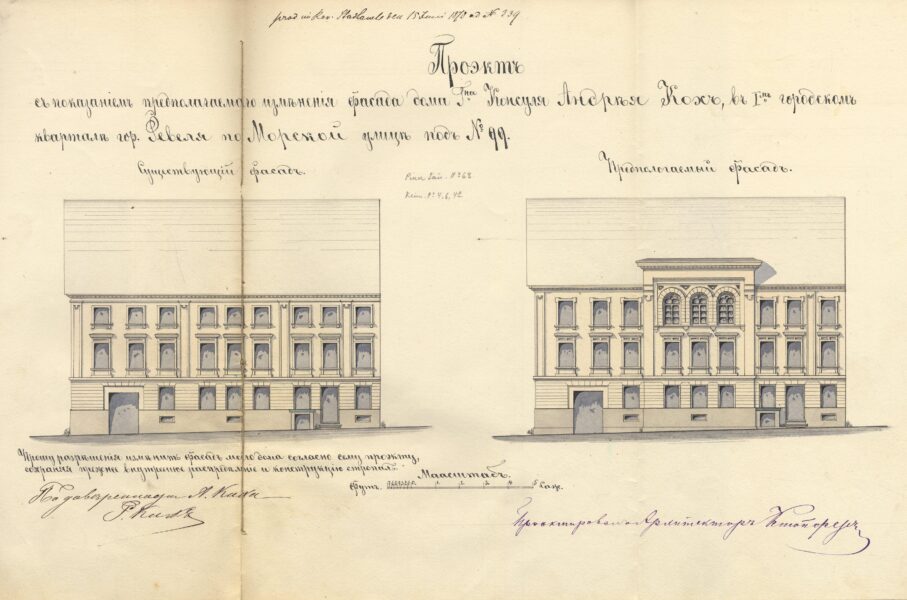

The property is first mentioned in 1419, when the then-owner, M. Brandeborch, transferred a unit inherited from his mother to Vlawes Hagenbock. Historical records from 1528 and 1545 refer to a “large house and a small corner house” on the site. The property also included the guardhouse of the Great Coastal Gate. In the first half of the 18th century, after the guardhouse was relocated, a large baroque townhouse was built in its place. In the mid-18th century, the property came into the hands of the Koch family, who retained ownership until 1920, when the Kreenholm Cotton Mill moved into the building.

The dates 1755 and 1878 on the building’s facade pediment indicate the times of major reconstructions. The earlier date likely refers to the period when the medieval gabled dwelling in diele-dornse layout (the “large house”) was combined with an adjacent outbuilding (the “small house”) and a gate structure. The later date marks a major renovation in 1878 (architect Rudolf von Knüpffer), which gave the building its current neo-Renaissance appearance.[25]

Within the boundaries of the property stands the Stolting Tower – part of the medieval town wall dating from the 14th century. The tower passed into private hands in the mid-19th century during the demilitarisation of Tallinn and was later incorporated into the Pikk 68 property.[26]

Today, the building complex houses the Avita publishing house.

Although the property is mentioned as early as the 15th century and its buildings in the first half of the 16th century, the house’s current appearance dates largely from the 1878 renovation.[27] At that time, a central section with arched windows and a stepped pediment was added. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Architectural plans of the building from 1878. (Tallinn City Archives)[28]

The ceiling of one first-floor room is as richly layered as the building’s history: six layers of paint have been identified here. Some are barely perceptible, but fragments of the first layer’s moresque ornamentation (blue ornamentation on a yellow background) have been uncovered, along with the second layer’s ribbon motif with a flower (greyish-blue ornamentation on a brown background framed by red lines). The visible sixth and final layer features swirling acanthus decorations on the beams and marbling in the spaces between.

The murals have been dated to the 18th century.[29]

The second paint layer features a ribbon motif adorned with a floral element, framed by red contour lines. The sixth paint layer features swirling acanthus ornament decorating the beams, with marbling in the spaces between.

The ceiling beam decoration extends onto the window lintel. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

In another first-floor room, the full-beam ceiling is covered with a rococo figurative mural. At its centre is a paradise-like blue sky with birds, framed by rococo ornamentation and a marbled surface. The mural was later covered with canvas, as evidenced by rows of nail holes in the beams.[30] (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Details of the rococo ceiling painting on the first floor. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

On the second floor, a rococo ceiling mural features a central rocaille motif – a shell-like element typical of the style – extending outward in four directions to form a framing composition. The spaces between the frames are decorated with marbling. The mural likely dates from the late 18th century. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room with beam paintings. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the rococo-painted room (on the first floor). (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the rococo-painted room (on the second floor). (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the 14th-century Stolting Tower (1st floor), situated on the property (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the 14th-century Stolting Tower (2nd floor), situated on the property (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the 14th-century Stolting Tower (3rd floor), situated on the property (Photo: Taavi Varm)

5] L. Künnapu, Arhitektuuriajaloolised eritingimused Pikk 68 siseruumide remondiks. Tallinn, 1997. Tallinn Urban Planning Department (TLPA) Heritage Protection Division, File No n1.538, no pagination.

[26] Arhitektuuribüroo Adrikorn & Rets. Kirjastus Avita büroo rekonstrueerimise projekt. Köide 1. Tallinn, 1998. Tallinn Urban Planning Department (TLPA) Heritage Protection Division, File No n1.538, no pagination.

[27] L. Künnapu, Arhitektuuriajaloolised eritingimused Pikk 68 siseruumide remondiks. Tallinn, 1997. Tallinn Urban Planning Department (TLPA) Heritage Protection Division, File N1.538, no pagination.

[28] Pikk 68 hoone projekt 1878. aastast. Tallinn City Archives, File NoTLA.1443.002.0000003.00007-T.

[29] K. Holland, Tallinn, Pikk tn 68. Maalingutega puitlagede konserveerimistööde aruanne. Tallinn, 2000. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n12.272, no pagination.

[30] K. Holland, Tallinn, Pikk tn 68. Maalingutega puitlagede konserveerimistööde aruanne. Tallinn, 2000. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n12.272, no pagination.

PIKK 69

The medieval merchant’s house on the corner of Pikk and Tolli Streets likely dates from the 15th century. The property, first mentioned in 1410, originally included two buildings: a dwelling and an adjacent warehouse. In the early 18th century, the warehouse was converted into living quarters and joined to the main house.

The dwelling retains its original diele-dornse layout. Unlike the usual design, however, the mantel chimney is not located in the corner of the diele but built as a separate unit. Also distinctive is the two-storey oriel, visible on the Tolli Street side, which is supported by stone corbels.[31] Both the oriel and several other rooms preserve historic painted beam ceilings.

In 1807, the property passed to the University of Tartu. A school was opened in the adjoining building, which had been added to the property. Later in the 19th century, the school expanded into the corner building. The second-floor storerooms were converted into classrooms, and the facade was altered.[32] Educational institutions continued to operate in the complex until the second half of the 20th century.[33]

At the start of the new millennium, the property was privatised. The entire complex was restored and now houses a hotel and restaurant.

While the building’s appearance largely dates from the 18th century, earlier origins are suggested by its massing, the corner buttresses, its steep gable roof and the loft loading hatch preserved from the former warehouse.[34] Inside, the house retains its medieval layout (diele-dornse), a mantel chimney, masonry staircase, beamed ceilings and even a medieval central heating system – a hypocaust stove and its warm-air vents.[35] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

During restoration works in 2008, researchers uncovered numerous culturally significant details, including ceiling paintings, carved window posts, masonry stairs and interior portals. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

In the room above the dornse and the adjacent oriel, painted beams survive, decorated with alternating grapevines and acanthus tendrils. The grapevine motif likely symbolises the Tree of Life – in Christian iconography, a reminder of the sacramental wine as the blood of Christ and a sign of redemption.[36]

In addition to the beam paintings, bits of canvas were found behind the cornice where the wall meets the ceiling, pointing to a once-present but now lost plafond mural.[37] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The ceiling of the small room of the two-storey oriel is also covered with paintings. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

From the late Middle Ages, windows became increasingly important in domestic architecture. Multiple windows were popular, with lintels supported by decorative carved stone posts. The window jambs – and later, the lintels – were often adorned with painted ornamentation (in the 17th century). The motifs on the lintels usually echoed those on the ceiling.[38] Carved stone supports became particularly fashionable in the late 16th and 17th centuries. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

A surviving carved stone column in the Pikk 69 house testifies to skilled craftsmanship. Its capital features a female head in frontal view, with coats of arms – likely those of the former owners – carved on either side. The base is supported by the head of a putto, or cherub, with traces of original paintwork revealing the column’s former decorative finish. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the little room in the oriel. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room with ceiling paintings and a carved window post. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[31] K. Särgava, Restor. Muinsuskaitse eritingimused Pikk 69 hoonekompleksi remont-restaureerimiseks. Tallinn, 2017. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9 10234, p. 8.

[32] T. Linna, Tallinnas, Pikk 69 hoonete A ja E säilitamisele kuuluvad arhitektuuriajaloolised väärtuslikud detailid ja konstruktsioonid. Arhitektuuriajaloolised väliuurimistööd. Tallinn, 1995. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n1.541, no pagination.

[33] L. Keskküla, M. Keskküla, Pikk 69 / Tolli 1 restaureerimine. – Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2019. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2019, p. 28.

[34] T. Linna, Tallinnas, Pikk 69 hoonete A ja E säilitamisele kuuluvad arhitektuuriajaloolised väärtuslikud detailid ja konstruktsioonid. Arhitektuuriajaloolised väliuurimistööd. Tallinn, 1995. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n1.541, no pagination.

[35] T. Linna, Tallinnas, Pikk 69 hoonete A ja E säilitamisele kuuluvad arhitektuuriajaloolised väärtuslikud detailid ja konstruktsioonid. Arhitektuuriajaloolised väliuurimistööd. Tallinn, 1995. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n1.541, no pagination.

[36] J. Kuuskemaa, Vana Tallinna pärimused ja tõsilood. Tallinn: Hea Lugu, 2020, p. 100.

[37] K. Särgava, Restor, Muinsuskaitse eritingimused Pikk 69 hoonekompleksi remont-restaureerimiseks. Tallinn, 2017. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9 10234, p. 22.

[38] K. Kodres, Kaunistatud elamu. – Eesti kunsti ajalugu 2. 1520–1770. Edited by K. Kodres. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2005, p. 141.

PIKK 71

The Three Sisters – a trio of steep-gabled houses standing side by side in Tallinn’s Old Town – are familiar to almost everyone in the city. These distinctive buildings were likely constructed in the first half of the 15th century. The oldest, the Big Sister (the corner house), may even date from the second half of the 14th century. It has been suggested that the Big Sister’s facade was influenced by the west gable of Pirita Convent: the house probably gained its current appearance in the early 15th century, when it was owned by Wulfard Rosendal. (The city wall tower behind the property – known as the Tower Behind Wulfard – is named after him.) Rosendal is known to have spent his final years at Pirita Convent, where he died in 1430, making the similarity between the buildings likely more than a coincidence.[39]

The Three Sisters are lined up, from left to right, in descending order of size: Big, Middle, and Little. All three houses follow the medieval merchant house layout with diele and dornse and were heated with hypocaust stoves.

Major renovations were carried out in the 17th century, including the carved baroque door of the Big Sister, whose panels display the family coats of arms of the master (J. Höppener) and mistress of the house. Significant reconstructions also took place in the 19th century.[40]

In the mid-19th century, A. C. Koch purchased all three buildings, which have since remained under unified ownership. The Koch family retained the ensemble until it was nationalised in 1940.[41] After the war, the buildings housed various administrative offices.[42] In the early 21st century, the Three Sisters returned to private ownership, underwent extensive restoration and were converted into a hotel. The complex continues to operate as accommodation today.

The Big, Middle and Little Sister. The most striking facade belongs to the Big Sister on the corner of Pikk and Tolli Streets, which features a baroque door from the 17th century. The entrance to the Middle Sister was once framed by a carved portal, which has since vanished.

The Little Sister’s entrance is on the courtyard side, which also affects the layout: the dornse (living quarters) faces the street, while the diele (entrance room) is on the courtyard side.[43] (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

In 2002, during restoration work, a full-beam ceiling mural was uncovered during the demolition of the courtyard-side building (probably built in the first half of the 18th century[44]), when plaster and canvas were removed. The rococo mural depicts two putti holding garlands of flowers, framed by ornate rocaille ornamentation. The painting is incomplete in the southwest corner, possibly because a structure such as a fireplace or cupboard was built there before the mural was painted. At the break point, an earlier mural layer with a similar composition is visible beneath the current painting.[45] (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Details of a rococo-style painting. (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

A wall painting in the diele window niche of the Big Sister was uncovered in the 1990s when a sealed window was reopened. The somewhat clumsy painting likely dates from the late 16th or 17th century.[46] (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

The ceiling beams in the dornse of the Middle Sister are decorated with a grey veined design imitating natural marble. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room with Rococo painting (featuring angel motifs). (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room with a painted window niche. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

Take a look around the room with marble-painted ceiling beams. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[39] B. Dubovik, Tallinn Pikk tn 71. Väliuurimistööde aruanne. Tallinn: State Design Institute for Cultural Monuments, 1983. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n3. 29, no pagination.

[40] R. Kangropool, Pikk tn 71/Tolli tn 2 hooneansambel „Kolm õde“ eritingimused rekonstrueerimiseks. Tallinn, 2001. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.645, p. 15.

[41] R. Kangropool, Pikk tn 71/Tolli tn 2 hooneansambel „Kolm õde“ eritingimused rekonstrueerimiseks. Tallinn, 2001. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.645, p. 18.

[42] R. Kangropool, Pikk tn 71/Tolli tn 2 hooneansambel „Kolm õde“ eritingimused rekonstrueerimiseks. Tallinn, 2001. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.645, p. 18.

[43] R. Kangropool, Pikk tn 71/Tolli tn 2 hooneansambel „Kolm õde“ eritingimused rekonstrueerimiseks. Tallinn, 2001. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.645, p. 8.

[44] K. Koppel, S. Volmer, OÜ Vana Tallinn. Hoonekompleksi „Kolm õde“ maalitud talalagede restaureerimistööde koondaruanne. Tallinn, 2003. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.2362.B, p. 4.

[45] K. Koppel, S. Volmer, OÜ Vana Tallinn. Hoonekompleksi „Kolm õde“ maalitud talalagede restaureerimistööde koondaruanne. Tallinn, 2003. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.2362.B, p. 4.

[46] E. Mölder, OÜ Vana Tallinn Suure õe aknaniši maalingu fragmentide konserveerimise aruanne. Tallinn, 2003. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9.2365, p. 3.

PIKK 73

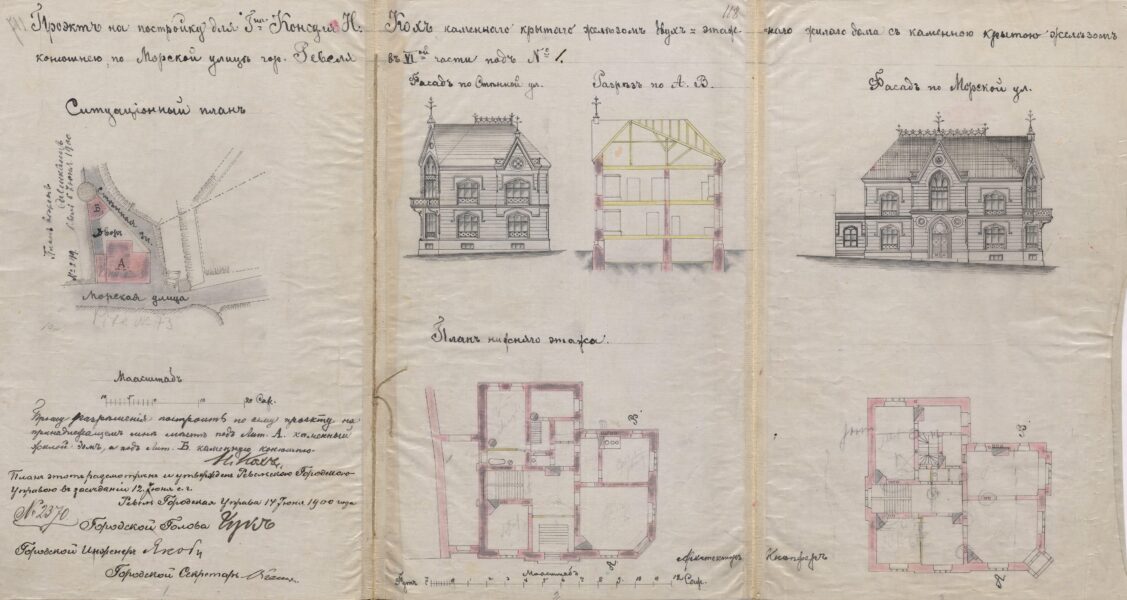

This two-storey townhouse, one of the most recent on the street, was built in the early 20th century on the commission of N. Koch (architect Rudolf von Knüpffer). It replaced a former police barracks; across the street stands the Fat Margaret tower, then used as the city prison.[47] The new building incorporates several fashionable styles of the time. The pointed arched windows and entrance door reflect neo-Gothic design; the triangular decorative gables on the side facades and corner allude to the English Tudor style; and the swirling plant motifs in the window frames recall art nouveau.

Throughout the 20th century, the building housed a variety of institutions, including the Sanitary Epidemiological Station, the editorial offices of the Publishing House of the Ministry of Culture of the Estonian SSR and of the Printing Industry of the Ministry of Culture of the Estonian SSR, the Estonian Journalists’ Union, the Committee for State Security of the Estonian SSR and the art museum’s storage department.

Historic architectural styles are also found inside the building. In the corner hall on the first floor, a vibrant art nouveau ceiling painting survives. It dates from the time of construction and was uncovered during restoration in 2007, hidden beneath layers of white paint.

Originally built as a city villa for the Koch family in the early 20th century, the house is now home to the Estonian Children’s Literature Centre and is open to the public. Visit to see the beautiful ceiling painting in person – and don’t miss the historic wooden staircase in the foyer. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

Architectural plans of the building from 1878. (Tallinn City Archives)[48]

The frieze of the first-floor corner hall ceiling is decorated with a repeating art nouveau floral pattern, while the corners and edges feature compositions of swirling plant motifs.

The cheerfully coloured central field is crowned by a white stucco rosette. Surrounding it is a garland of flowers with little bows, dating slightly later – probably from the building’s first renovation, before 1914.[49] (Photos: Tõnu Tunnel)

Take a look around the room. (Photo: Taavi Varm)

[47] A. Pantelejev, Tallinn, Pikk t 73 hoone osalise remont-restaureerimise muinsuskaitselise järelevalve aruanne. Tallinn, 2014. TLPA Heritage Protection Department Archive, File No n9. S. 9786, p. 1.

[48] Pikk 73 hoone projekt 1900. aastast. Tallinna Linnaarhiiv, säilik TLA.1443.002.0000002.00005.T.

[49] A. Pantelejev, Tallinn, Pikk t 73 hoone remont-restaureerimise muinsuskaitselise järelevalve aruanne. Tallinn, 2008. This report is held by the Estonian Children’s Literature Centre. No pagination.

Pikk Street

HIDDEN HERITAGE

Compiled by Karola Mursu

Photographs by Tõnu Tunnel

Historical photos: Estonian History Museum, Estonian Museum of Architecture, Tallinn City Museum

360° photos: Taavi Varm

PIKK STREET

Since the Middle Ages, Pikk Street was one of Tallinn’s most important thoroughfares. Stretching from the gate tower at Pikk Jalg Street to the Great Coastal Gate, it was a vital artery between the city and the harbour. The layout of the streets and division of plots in this area largely date back to medieval times. Narrow, elongated plots extend from the street into the depth of the block and, in the case of larger plots, all the way to the next street. In the Middle Ages, Pikk Street was lined with rows of gabled houses whose triangular facades stood shoulder to shoulder like a row of saw teeth.

Pikk Street. (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

The typical medieval dwelling was a Hanseatic merchant’s house, with a narrow, tall facade and steep gable facing the street. The warehouse was often located on the street side, while the living quarters were arranged around a courtyard further back on the plot. The first floor housed the diele, a spacious front room with a mantel chimney in the corner that also served as the kitchen and where guests were received. Behind the diele, closer to the courtyard, lay the dornse, a more private space for the family’s daily life and rest. Over time – by the 17th century – the living quarters expanded to the upper floors, replacing the storage spaces. These rooms were accessed via a stone staircase situated between the diele and dornse.[50]

Medieval dwelling with a diele-dornse room layout. (T. Böckler)[51]

This part of the city was home mainly to craftsmen and foreign merchants.[52] The craftsmen’s houses were smaller and simpler than the merchants’ residences, with more modest courtyards or none at all. Unlike merchants, craftsmen had no need to keep horses, so they had no use for a stable or large yard.[53]

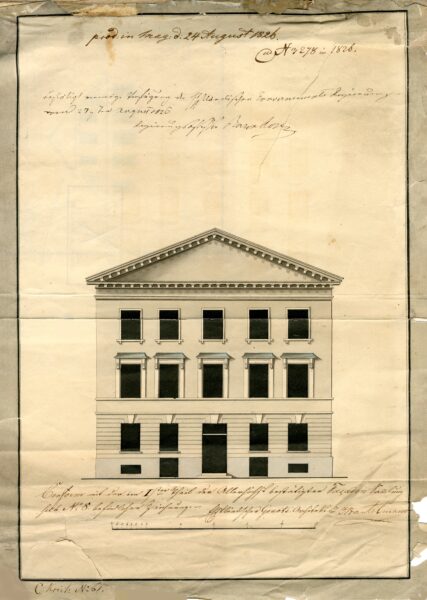

Pikk Street retained its saw-toothed appearance for a long time. The first major changes came in the 18th century with the arrival of Palladianism, inspired by ancient art and architecture, which brought early neoclassical townhouses to the street.

Old Town block no. 5 (Pikk, Pagari, Lai, and Oleviste streets). Facade drawings from the 1825. (Russian State Military History Archive)[54]

In 1809, the Russian Empire introduced standardised facades to be applied across the country, and these were soon enthusiastically adopted and regulated in Reval (Tallinn’s historical German name). The city’s medieval merchant houses were seen as outdated and were redesigned in line with the new classical ideals. Window and door openings were relocated and rooflines reworked. Often, several small medieval buildings were merged behind a single new facade. Gothic forms and ornamentation were frequently left in place beneath the new exterior layer. Today, many of these hidden medieval features have been uncovered and displayed during restoration works.

Renovation projects adapted to the standard facade from 1826, architects Bantelmann, Schellbach ja Gabler. (Tallinn City Archives)[55]

View of Pikk Street from the Great Coastal Gate. (Photo: Estonian Museum of Architecture)[56]

[50] S. Karling, Tallinn. Kunstiajalooline ülevaade. Translated by Beekman, V. Tallinn: Kunst, 1937, pp. 66–69.

[51] Medieval dwelling with a diele-dornse room layout. Excerpt from a drawing. – Böckler, T. Eesti kunsti ajalugu 2. 1520–1770. Edited by K. Kodres. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2005, p. 106.

[52] S. Karling, Tallinn. Kunstiajalooline ülevaade. Translated by Beekman, V. Tallinn: Kunst, 1937, p. 38.

[53] J. Kuuskemaa, Maailmapilt (radio programme). 13 June 2000. ERR Archive: https://arhiiv.err.ee/audio/vaata/maailmapilt-maailmapilt-juri-kuuskemaa-34195 (accessed 15 June 2025).

[54] Old Town block no. 5 (Pikk, Pagari, Lai, and Oleviste streets) from a 1825 survey drawing. Facade drawings from the 1825 archives of the Russian State Military History Archive. – H. Üprus, Tallinn in the Year 1825. Tallinn: Kunst, 1965. Pages unnumbered.

[55] Renovation projects adapted to the standard facade from 1826, architects Bantelmann, Schellbach ja Gabler. Risse zu Privathäusern von den Gouvernements Architekten Bantelmann, Schellbach und Gabler. Tallinn City Archives, File NoTLA.149.4.321, sheet 14.

[56] View of Pikk Street from the Great Coastal Gate. Estonian Museum of Architecture, File No EAM Fk 12523. Museums Public Portal: https://www.muis.ee/museaalview/2638803 (accessed 29 July 2025)